Following a long lull to accommodate one of the UK’s wettest October-March periods on record (see https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cp992nxxe7do), the final phase of the Joy Welch project (“Giving Voices to Rivers: Promoting Creative Engagements Through Art-Science Collaborations”) finally got underway. This phase is designed to promote creative engagement with rivers in outdoor settings.

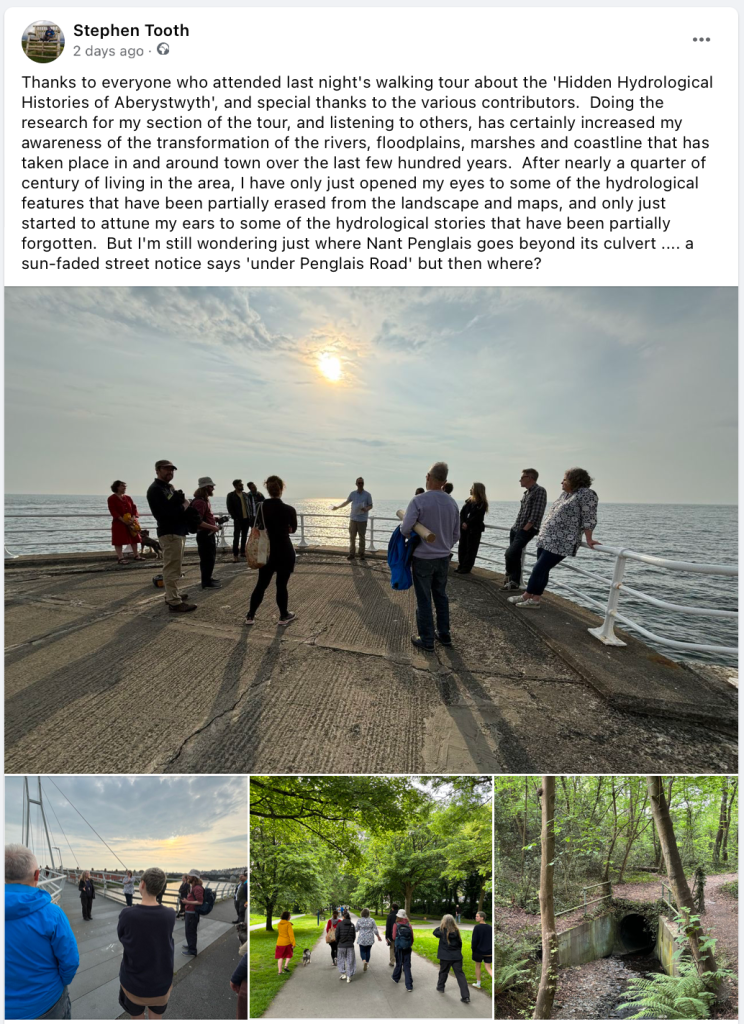

On Tuesday 21st May 2024, Hywel Griffiths and myself were joined by 13 other people for a walking tour to uncover the ‘Hidden Hydrological Histories of Aberystwyth’. Most of these people were university staff or students (a range of departments were represented, including from the arts, humanities, and sciences) but we were also joined by some people from outside the university, including local artists. The purpose of the tour was to highlight some of the little-known or largely forgotten facts, stories, and lore about the local riverscapes, floodplains and shoreline, while also raising awareness of the profound human-induced environmental changes that have taken place in recent centuries.

Getting to this point had been an interesting journey for me. I have now lived in and around Aberystwyth for nearly a quarter of a century but with my mind preoccupied by environmental and landscape changes in other parts of the world, I had not thought too deeply about the changes closer to home. Over the last couple of years, however, doing research for a potential walking tour had certainly made me look at, and think about, my local environment very differently. Among various reflections, I had pondered how the local environmental and landscape changes over the last few centuries connected with wider social and economic trends affecting west Wales, the wider UK, and indeed the world, most notably the spread of the industrial age and European colonial expansion. Would the tour provoke similar reflections among those present, while also stimulating ideas for engagement and creative practices with rivers and related watery environments?

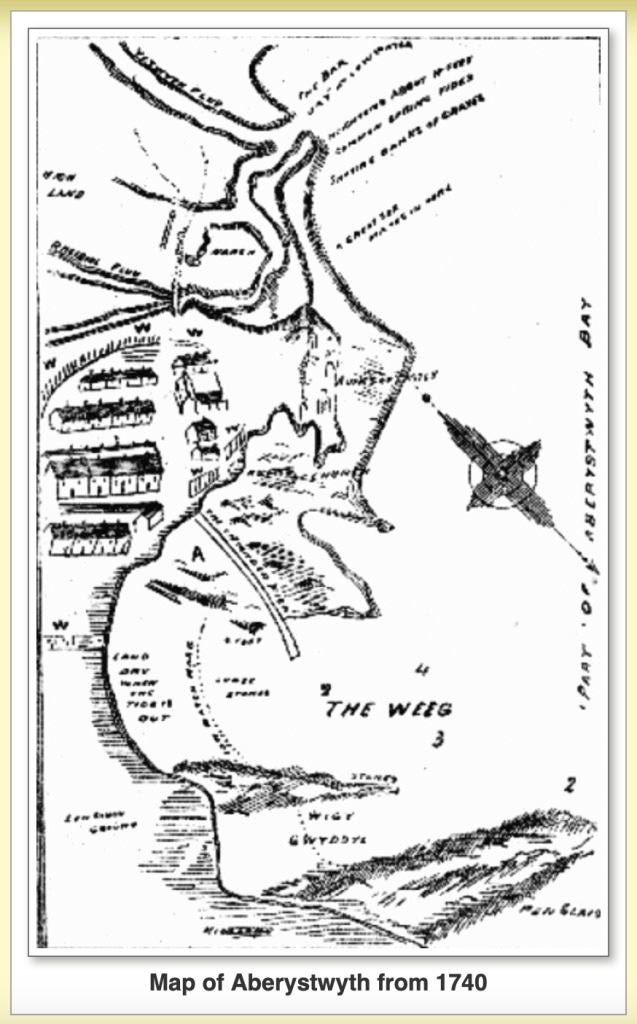

After an introduction to the background and motivation for the Joy Welch project, the tour started with my outline of the rapid transformation of the local rivers, floodplains, marshes, and beaches that has taken place since Aberystwyth began to expand beyond its medieval town walls at the very end of the 1700s. Some of the earliest maps of the region show that until this time, the town was surrounded by marshes to the south, east and north. The marshes were the frequently flooded floodplains of the Afon Rheidol or coastal backbarrier environments and had various names, which appear on some of the earliest maps or in other archival sources: Morfa Bach (Little Marsh), Morfa Mawr (Big Marsh) and Morfa Swnd (Sand Marsh). Until the early 1800s, people travelling between Aberystwyth and Llanbadarn commonly had to be rowed across particularly wet parts. But with the town’s expansion, these marshes were gradually enclosed, drained, and built over. Many of these hydronyms disappeared from maps, while anglicisation has also partially erased memories of this early hydrological history: as an example, one street remains as ‘Morfa Mawr’ in Welsh but has become ‘Queen’s Road’ in English. Other older hydronyms and water-related toponyms also have largely been lost (e.g. Morfa Hallt, Ro Wen, Ro Fawr) but some older ones linger on in house names, street names, or place names (e.g. Sandmarsh Cottage, Chalybeate Street, Bryn y Mor Dingle).

Other aspects of the hydrological history are seemingly harder to reconstruct, at least in detail. Local lore – bolstered by reinforcement in some reports and publications – says that the lower Ystwyth River was diverted or re-aligned and straightened as part of the harbour improvement works of the late 1700s and early 1800s. The apparent idea was to use the flow of the Ystwyth to scour the sand bar at the entrance to the harbour that was proving to be a nuisance, or even a hazard, for seafaring vessels. But the map and documentary evidence is less clear than one might expect. Some early maps (mid 1700s) show the Rheidol and Ystwyth following separate paths to the coastline, hence suggesting a possibility that the Ystwyth was later diverted or re-aligned and straightened to join the Rheidol at the harbour, but other sketches and maps from the same time period distinctly show both rivers already joined in the harbour. The hydrosocial events of this period can inspire creative responses: on the walking tour, a reading of a poem by Hywel entitled ‘Tan-y-bwlch’ harked back to bygone days when ships would be waiting in the bay for their turn to enter the harbour and load up with the spoils of lead, silver and other minerals extracted from the Aberystwyth hinterland.

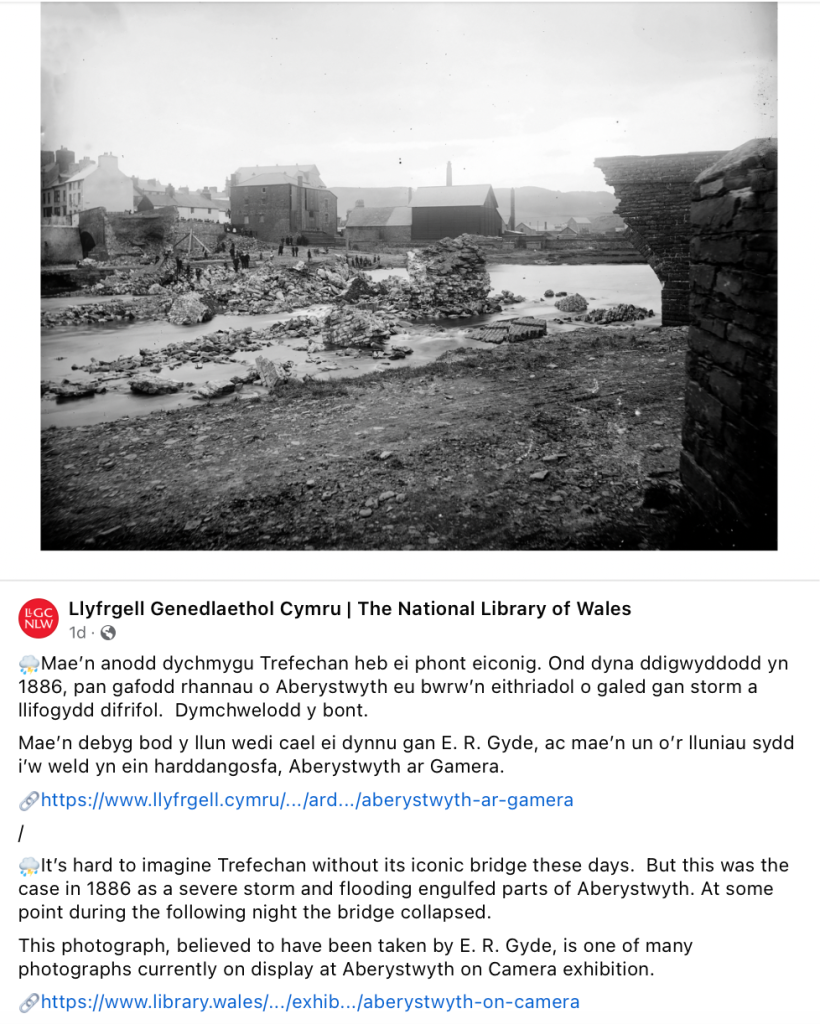

Other hydrological histories can be revived through inspection of archival sources and attention to the present-day landscape. On present day Mill Street, for instance, a former mill was powered by water running along a leat: an open water course that was built to convey water from the Rheidol. The mill was located near Trefechan Bridge, which spans the Rheidol. The bridge is well known for its role in social history – specifically having played a pivotal role in the early stages of the Welsh language protest movement just over half a century ago (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-wales-21316103) – but also has an interesting hydrological history. The original late 18th century stone bridge – designed by John Nash, one of the foremost British architects of the Georgian and Regency eras – was destroyed by a major flood in late 1886. The devastation was captured in newspaper reports and other florid accounts as well as in a few early black-and-white photographs that periodically circulate on social media. Again, this hydrological history can inspire creative responses: during the walking tour, a reading of one of Hywel’s Welsh medium poems (‘Pont Trefechan’) evoked some of the emotions that might have been felt by those witnessing the original bridge’s destruction by the flood. In the flood’s aftermath, such was the fear of a cholera outbreak that an October 1886 notice ‘To the Householders of the Borough of Aberystwyth’ from the Medical Officer of Health implored all flood-affected property owners to clean, thoroughly disinfect, and dry their walls, floors and clothes.

The remainder of the tour largely revolved around contributions from some of the other people present, and focused more on the histories that are yet to fully unfold. Standing on the much younger Trefechan Footbridge that spans the Rheidol slightly more than a stone’s throw upstream of the main Trefechan Bridge, Sarah Davies highlighted the pioneering contributions of Kathleen Carpenter to the study of the freshwater ecology of rivers in west Wales (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_E._Carpenter), while Chloe Griffiths spoke about the findings from more recent, citizen science river monitoring projects. Despite a legacy of mining pollution that affects the Rheidol and some other rivers in the areas, success stories can be noted – the beautiful demoiselle (a large damselfly) apparently is doing well, and a population of otters has remained on the Rheidol – but many challenges remain. Water vole activity, for instance, has been detected in recent years but these endangered mammals may be struggling to maintain a viable population in the face of predation from mink. Brian Swaddling outlined his ongoing creative project to weave excerpts from the various ‘voices about the river’, including some of those voices that were being heard on the tour.

A short walk from the Rheidol took us to Plas Crug, now the site of a local primary school built on a rocky outcrop. Once upon a time, this outcrop would have provided an island of drier ground above the local marshes. Paintings from the 1700s provide a sense of the former hydrological landscape, and are complemented by other archival sources that record subsequent changes. As an example, the year 2024 marks the bi-centennial of the publication of T.J. Llewelyn Prichard’s book entitled ‘The New Aberystwyth guide to the Waters, Bathing Houses, Public Walks, and Amusements; Including Historical Notices and General information, Connected with the Town, Castle Ruins, Rivers, Havod, the Devil’s Bridge, and all Places of note or Interest Adjacent’. A lengthy title indeed, but the text itself is more digestible, with some passages noting the hydrological transformations that were taking place by that time. A section on Plâs Crûg, for instance, notes that:

“Crûg, means a hillock, or ground rising suddenly from a flat, which is precisely the description of this place; and there could not be a more characteristic name for it than Plâs Crûg, or the Palace of the Mount ….

Here the river separates, forming an island, not quite two miles in circumference, called Y Morva, or The Marsh, which formerly, after heavy rains, used to be entirely flooded; but of late years it has been drained and embanked, and is now considered excellent arable and pasture land.” (p.54).

This separation of the river is probably linked with the aforementioned leat that conveyed water to the former mill. The point of diversion from the Rheidol is unknown but the open ditch through modern-day Plas Crug Park probably closely traces the middle section of the leat. With the town’s expansion, the leat’s downstream section also has now been built over, so here too its precise course is uncertain. Uncertainty remains over the course of other local rivers too: Nant Penglais, for instance, emerges from the wooded Penglais Dingle, and enters a culvert that is said to go ‘under Penglais Road’ …. but then to where? Does it follow a southwest course to join the leat and then the Rheidol or does it stick to a more westerly course to directly enter the sea?

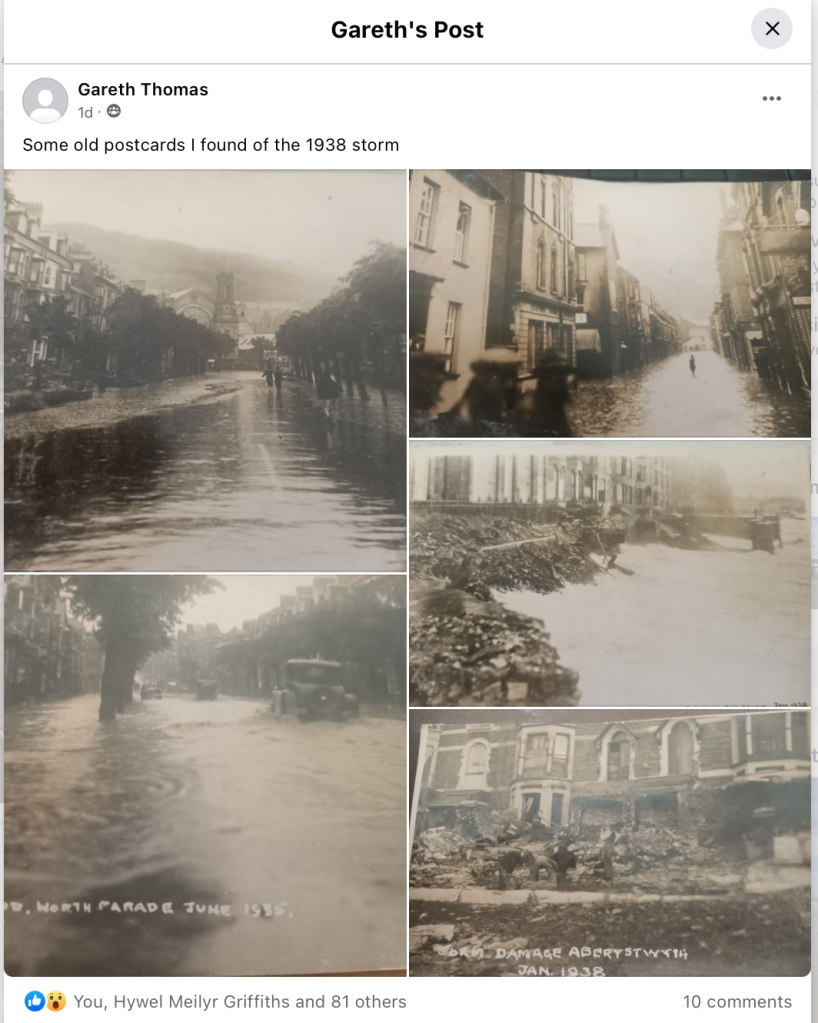

These hydrological mysteries aside, it is clear that the town’s extension onto the former, low lying marshy environments over the last 200 years or so is closely linked with some of its more modern flooding problems. Old photographs and reports of recent flash flood events (https://www.cambrian-news.co.uk/news/999/thunder-storm-causes-flooding-in-aberystwyth-town-centre-110290) show that the centre of the modern town has frequently been inundated following heavy rain, river flooding, and coastal storm surges. And as the walking tour drew to a close, local artist Rob Davies highlighted the future problems that may be in store. Topographic surveys show that many streets in the modern town centre lie up to several metres below the February 2023 spring high tide level. As the BBC article hyperlinked at the start of this post has highlighted, the UK’s autumns, winters and early springs seem to be getting warmer and wetter. Coupled with ongoing sea level rise and projected future increases in coastal storms, this leaves parts of the town centre very vulnerable to future flooding.

Can we use creative approaches to highlight to the people of Aberystwyth the nature of this particular hydrological challenge? Rob has his ideas for an innovative visual installation that might help raise awareness about the flooding threat from sea level rise and stimulate positive discussions about adaptation and mitigation options. He has the support of some local town councillors, but still requires permission from local businesses to be able to realise the installation, at which point details can be made public. Nevertheless, and just as I hoped, from the ensuing discussions that took place between those present on the tour it is clear that Rob’s proposal had provoked reflection and stimulated ideas for engagement and creative practice.

With respect to flooding, perhaps Aberystwyth can be said to be carrying the curses of both history and a history still to be written.1 But by highlighting some of its hidden hydrological histories, paying closer attention to changes along local rivers and coastlines, and debating adaption and mitigation options, we can at least face the future better forewarned and maybe even better forearmed.

———————-

1 Adapted from lyrics to New Model Army’s ‘Here Comes the War’ (songwriting credits attributed to Sullivan/Heaton/Nelson, 1992)